Sphinx Temple and Valley Temple

Two megalithic structures are found in front of the gigantic Sphinx, which in turn lies in front of the three large Giza pyramids like a watchdog and looks away from them directly towards the East.

Both these structures were unknown until the mid-19th century because they were entirely covered by sand and soil. The Valley Temple was discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1853. He used dynamite to excavate the site, destroying important sections in the process. Because the Valley Temple, nevertheless, has more to reveal than the Sphinx Temple, and as a megalith structure in the middle of Giza plays a key role in terms of building techniques as well as the worldwide connection of those who built it, we will describe it in detail here.

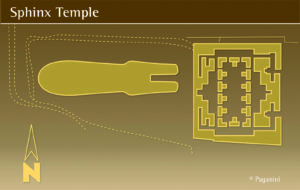

The Sphinx Temple

Situated directly in front of the Sphinx, consisting of limestone blocks weighing up to 200 tons, is what is today referred to as Harmachi’s Temple, or simply the Sphinx Temple. Diagonally in front of the Sphinx, to the right if you are looking from behind it, at the beginning of the Causeway to the Pyramid of Chephren, is the so-called Valley Temple of Chephren, although this provenance remains unproven and is thus arbitrary.

The Valley Temple

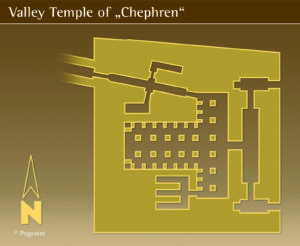

Just like the three large Giza pyramids, the Valley Temple is perfectly oriented along the north-south axis. It is nearly square, with sides measuring approximately 45 meters / 147.6 feet. The entire structure is level, although the rocky foundation is elevated on the western side. The eastern wall is therefore twice as high (nearly 13 meters / 42.6 feet) than the western wall (around 6 meters / 19.7 feet). The roof, which only remains in place in one corner, was thus absolutely horizontal.

The structure appears like a square mesa in which several corridors and rooms have been sectioned off. The walls are made of gigantic pink granite blocks. The back sides of the walls were lined with blocks made of the local limestone. Depending on which construction method is assumed to have been used, it can be said that the limestone blocks form the core wall construction which was encased inside and out with pink granite blocks.

On the east side of the temple, which can also feasibly be described as a castle or fortress, there is a 6 meter / 19.7 feet high niche from which a 2 meter / 6.6 feet taller corridor leads inside. The original façade made of pink granite is extensively destroyed so that today only the limestone core can be seen. The entrance leads to an antechamber with walls, floor and ceiling made of granite blocks. From there a corridor veers off at a right angle to the first cross hall, the floor which, as in all the other halls of the Valley Temple, is tiled with white alabaster.

The T-shaped central hall is reached through a corridor in the middle of the eastern wall, where sixteen undecorated monolithic columns stand. Borne across the tops of these were once massive stone blocks that most likely held up the roof plates. Many of these crossbeams are missing today. The most recent plundering took place in 1860, when August Mariette had several granite architraves blown up with dynamite. Found in the western section of the Central Hall, stretching over five sections of the wall are 23 rectangular insets into the alabaster floor. It is assumed that statues once rose from these insets.

Possibly they were like the diorite seated statue that was found upside down in a well-like hole in the 19th century, which bears inscriptions indicating that it represents the Pharaoh Chephren. This find has led Egyptologist to believe that Chephren built the Valley Temple. This belief was reinforced by the existence of the causeway leading to the Pyramid of Chephren. However, in no place within this megalithic structure was ever the inscription of a pharaoh found.

Inside the T-shaped room, to the left and to the right, corridors branch off leading to the west. The southern corridor leads to a three-sectioned, two-storey niche chamber. The northern corridor is the exit leading to the 495 meters / 1624 feet long causeway. Two side corridors branch off at the midpoint of this exit corridor. The northern one leads to what formerly was the roof, while the southern side corridor is interpreted today as having been the doorkeeper’s chamber. The entrances to both side corridors are blocked with wire-mesh doors today. Behind the mesh in the southern side corridor lies the impressive monolithic construction of the wall that turns sharply to the west after 2 meters / 6.6 feet. Remarkable is the pink granite wall, which is hardly ever mentioned in the Egyptian text books and rarely documented photographically.

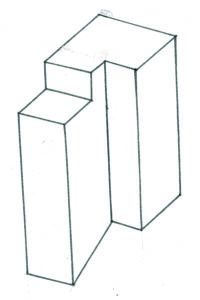

The megaliths are up to 9 meters / 29.5 feet long, 3 meters / 9.8 feet high and 4 meters / 13.1 feet wide, weighing 100 up to 300 tons each! These stone blocks can be found as high as 10 meters / 32.8 feet tall. Their shape is also amazing; each one is cut into a polygonal shape and fit together in a tongue and groove pattern, in places above the edges of the wall.

This extremely complicated manner of building is inconceivable without the latest stonecutting equipment and cranes. Nevertheless, Egyptologists consider it entirely plausible that the pharaohs were capable of such construction mastery, which from a contemporary view seems absurd, assuming that they had the time and money and nothing better to do.

This is an excerpt from the book GIZA LEGACY.