Pyramids in China

China’s pyramid culture has been around for millennia, and you would be amazed at the number and size of the specimens and the vastness of the variety that have been discovered there in the last 70 years alone.

Pyramids near Xi’an

While Xi’an is not in the western region of the Taklamakan, we will nevertheless begin our overview here in central China, because it is the origin of the prehistoric Banpo culture (see page 610). The capital city of the Chinese province of Shaanxi is today one of the 15 sub-provincial cities in China and is home to almost eight million people. But in 250 BC, Xi’an was already the capital city of the first empire and home to further emperors over the course of the next 1,120 years. It was usually referred to by the name “Chang’an”, which means “constant peace”. It was the seat of the Qin Dynasty when, in the year 221 BC, it completed its conquest of all rival kingdoms and united the entire Chinese territory under a single emperor for the first time. The city of Chang’an of the Han period lay about 5 km northwest of the modern-day city and was home to around 240,000 inhabitants at the beginning of our era. In 18 AD, the city was devastated in the “Red Eyebrow Rebellions”, upon which the emperor’s family moved their capital to Luoyang. Construction of the huge new capital city of Daxing was begun near modern-day Xi’an in 582 AD under the first Sui emperor. It became the largest city in the world in 618, under the subsequent Tang Dynasty, covering 88 square kilometers and sheltering one million inhabitants. During this period, it was given the name Chang’an once again, but was renamed Xi’an in 1369 by Hongwu, the first Ming emperor. The city center is still encompassed by a huge, nearly completely preserved city wall from the early imperial period.

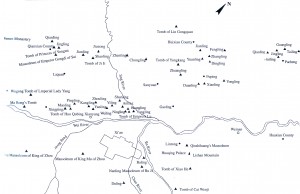

Xi’an’s “Valley of the Kings” stretches from the Sichuan Plateau (Quin Chuan) almost 120 km along the Wei Ho River and served a function for China similar to that of the “Valley of the Kings” near Luxor for the Egyptian pharaohs; there are over 100 pyramids around Xi’an. I prepared for my journey there for three years and, after completing all the paperwork and jumping through the bureaucratic hoops, was finally able to experience and explore this place myself. The satellite images of the pyramids there looked promising and large, much like those in Egypt and South America. But after a difficult journey, I was initially disappointed because from the ground and from the side, the gradual nature of the slopes of these pyramidal structures is very obvious – most have an angle of less than 10°. They were made of piled-up boulders and earth, and thus suffered greatly from erosion. These “pyramids” are not built of stone blocks, like the three megalithic pyramids in Giza or those in South America, where the other two lines of the Atlanteans’ descendants settled. The third line settled within the triangle of India, Tibet and China (see GIZA LEGACY, page 112).

The pyramids there are defined according to the following criteria:

– They were built on the earth’s surface from stone blocks and are between 30 and 146 meters high.

– The stone blocks used were carefully cut to size and processed.

– The pyramids contained chambers or lie above underground chambers.

– Construction was oriented towards the four cardinal directions.

But the Xi’an pyramids meet almost none of these criteria:

– They were made by piling up boulders, earth, and clay and are between 25 and 85 meters high.

– A very few were made of clay bricks (much like the 1,000 or so grave pyramids in Egypt). Most were made of earth that was piled up and tamped down.

– Some were shaped from existing natural hills.

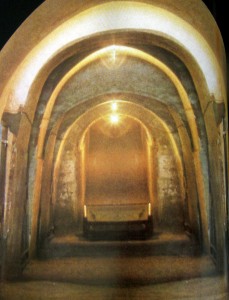

– Only a few have subterranean complexes with passages and chambers, but those are noteworthy and beautiful (see Fig. 14.32 and 14.33).

This means that these earthen pyramids do not originate from a prehistoric culture and are not megalithic. The pyramids in Xi’an really are burial pyramids, like almost all clay pyramids in Egypt (excepting those upon which the Xi’an pyramids are patterned, the megalithic pyramids in Giza, which never were used for burial). According to Chinese archaeologists, they are “grave mounds” of rulers from the Western Han Dynasty from 206-220 AD, and thus about 1,800 years old. A few Chinese archaeologists say they are 2,500-3,500 years old, constructed between 1,500 and 500 BC, the time of the legendary “emperors of prehistory”.

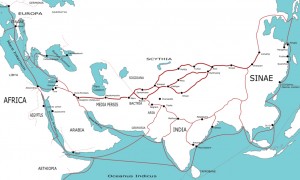

But how did the Chinese get the idea, suddenly and in this valley, to build pyramids for the burial of their emperor’s family? At first, I assumed that the knowledge had been passed down. Perhaps they were also inspired by the Banpo culture with their pyramid houses or by the great pyramids that today are no longer standing or have not yet been discovered. But then – on a journey through China along the Silk Road, from Xi’an to Taklamakan and from Dunhuang to Hotan – I became conscious of another, more likely influence. This connection between China and Europe has been documented to have existed since the beginning of the Bronze Age, between 2,200 and 800 BC, and primarily served the exchange of extracted and worked metals and various trade goods. Our oldest accounts of the Silk Road come from ancient Greece and Rome in Herodotus’ detailed descriptions, dating from 430 BC, of the northern route and all the major communities with the peoples who lived there. Direct trade among Xi’an, the far east, the Middle East, Egypt and Europe, and the cultural interaction of all these civilizations, is documented from around 300 BC (see page 602 and Fig. 14.48). The first pyramid is said to have been begun by Emperor Qian Shi Huang in 246 BC, so it is quite possible that merchants and imperial emissaries brought their reports and drawings from Egypt, reflecting the impressive structures in Giza and the clay-brick burial pyramids of the families of the pharaohs of the period. This may have inspired Emperor Qian Shi Huang to build the first – and naturally, larger – pyramid according to the example and construction methods of the Egyptians.

The three exceptional pyramids around Xi’an, constructed using three different methods:

1. The Qian Shi Huang pyramid (Qin Dynasty) constructed of clay bricks

The first and largest “burial pyramid” is thought to be that of the first Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who unified China as a country and founded the Qin Dynasty. It lies in the huge mausoleum at the foot of the Qing Ling Shan Mountains, 80 km southwest of Xi’an. He began construction as soon as he ascended the throne at the tender age of 13 in 246 BC. It was to be of tremendous dimensions – its base was 354 x 357 meters, and its original height was 200 meters, making it the largest “pyramid” in the world (for comparison, the great pyramid in Giza is 230 x 230 meters and 147 meters high). For the 36 years that work went on, up to 700,000 people were employed at the site at a time to construct the pyramid and the subterranean complexes over an area of several thousand square meters. Construction was completed in 210 BC.

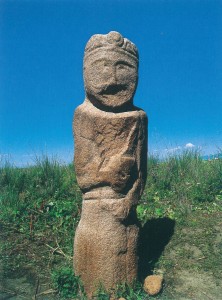

2. Qian Ling pyramid (Tang Dynasty), formed from a hill

This pyramid and the burial complexes are located on the slopes of Mount Liang, 6 km north of Quianling, the county seat, 80 km northwest of Xi’an. It is the mausoleum of the third Tang emperor, Gaozong (650-683 AD) and his wife, who became the Empress Wu Zetian (684-704, seventh daughter of Emperor Zhongzong (Li Xian), who was buried there in 684 or 706. The “pyramid” was not made by piling up material, however, but by shaping an existing hill (resulting in a “shaped pyramid”) which is not square and has large differences in its base lengths. What is special is the emperor’s subterranean burial chambers, which belie influences that are atypical for early China (see Fig. ??). Of the 18 Tang emperor burial sites in the Guanzhong Plain, it is the only complex that was not found and plundered by grave robbers. The enormous stairway access is almost 2 km long with two bulwark towers in front of the “pyramid” and is flanked by figures of animals and people that are up to 4 meters high and by monolithic stone pillars. Among these are armed guards, winged horses (yima), stone lions (shishi) and the Shusheng Tablets and Uncharactered Stele (wuzibei).

Earthen Pyramid of Princess Yongtai (Tang Dynasty)

Princess Yongtai (Huang Ti) was the granddaughter of Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu Zetian, and died in 701 AD at only 17 years of age. She was buried near the Qianling Mausoleum in 706, together with Prince Duwei Wu Yanhin, a nephew of Wu Zetian who had died one year earlier (this delayed burial was possible because the bodies had been mummified).

Yongtai‘s grave is surrounded by strong, 3-meters-tall walls, oriented to the four cardinal directions. They are 275 meters long from north to south and 220 meters wide from east to west. The pyramidal hill is located in the middle of the mausoleum. Today, it is only 14 meters high, with a respectable side length of 56 meters. An arched corridor 88 meters long, almost 4 meters wide and 6 meters high leads from the southern entrance to an antechamber and from there to the actual burial chamber. This one impressed and surprised me even more than that of Emperor Gaozong; it corresponds almost exactly to the Egyptian construction method. These similarities are not limited to the long corridors leading below the pyramid, but also include the chamber‘s shape and especially the outer sarcophagus. It is made of black basalt and is almost identical to the 24 sarcophagi in the Serapeum of Sakkara (see page 92). The frescoes are also exceptionally well preserved. The burial chamber‘s east and west walls are covered with depictions of black dragons, white tigers and an honor guard, and the ceiling features astronomical motifs. The antechamber‘s east and west walls bear depictions of waiting servants. This tomb is believed to have been plundered very early. Nevertheless, more than 1,300 items have been discovered in the vicinity during the past 50 years, including gold- and silverware, glazed figurines, porcelain and copperware.

3. Earthen Pyramid of Mao Ling (Han Dynasty)

This burial site is located 40 km from Xi‘an, near the village of Maoling, northeast of the city of Xingping. The mausoleum of Mao Ling, the burial pyramid of Emperor Wudi of the Han Dynasty (141-87 BC) is the largest of the five mausoleums built during the Western Han Dynasty and is also called the “Pyramid of the East”. Its construction is thought to have begun in 139 BC and lasted 53 years. It was surrounded by a square bulwark wall almost 6 meters thick, 431 meters long east to west and 415 meters long north to south. There was one gate in the middle of each section of the wall, one for every cardinal point. The central burial mound is a truncated pyramid, eroded to a height of 46.5 meters, with a base of about 217 x 222 meters.

Around the central mausoleum are over 20 other tombs for Wudi’s family, ministers and generals, such as the burial pyramid of generals Huo Qubing, Wei Qing and Jin Midi, located between 1 and 2 km east of the emperor‘s tomb. Today, the complex also features the Mao Ling Museum, where splendid burial objects are displayed; historical records claim that the emperor spent one third of all tax income for several decades on the mausoleum‘s construction and his family’s burial goods.

The “White Pyramid” near Xi’an

The White Pyramid, as it is called, is also reportedly located near Xi’an and has become world-famous over the past 20 years even though there is still no proof that it exists. So let us shed some light on this legend.

1912

Several books and sources on the internet feature the following fascinating yet undocumented story: In 1912, Australian merchants Fred Meyer Schröder and Oscar Maman traveled to Sichuan Province. They were the first Western travelers to discover over one hundred pyramids found there. There was one huge pyramid they found especially fascinating. The two travelers estimated its base length at 1,500 feet (450 meters) and its height at 1,000 feet (300 meters). Schröder also reported that each of the pyramid‘s four sides was of a different color. The north side was black, the east blue, the south red, and the west white, while the pyramid‘s flat summit was covered with yellow earth. They questioned the leaders of the local monastery about the pyramids and were told that they were first mentioned 5,000 years ago (around 3,000 BC) and were therefore presumed to be even older. The Australians also reported that these pyramids might stem from the time of the legendary emperors (1,500-500 BC), who believed themselves to be descended from extraterrestrials whom they called “children of heaven” who landed on Earth in “dragons of iron”. These ancestors also built the first pyramid. Still, there are no sources or original documents mentioned anywhere, although some points seem plausible and could well be true.

1945

The most common account of the White Pyramid is based on a report from 1945, during World War II, which remained confidential until 1990. It contained a statement by US Air Force pilot James Gaussmann, who claimed to have seen an enormous white pyramid while flying from India to China. But the file contained no photographs or maps. This is the original report:

„I banked to avoid a mountain, and we came out over a level valley. Directly below was a gigantic white pyramid. It looked like something out of a fairy tale. It was encased in shimmering white. This could have been metal, or some sort of stone. It was pure white on all sides. The remarkable thing was the capstone, a huge piece of jewel-like material that could have been crystal. There was no way we could have landed, although we wanted to. We were struck by the immensity of the thing.“

(14.2 – Gaussman)

1947

It has come to be assumed that these reports are based on another story, that of Colonel Maurice Sheahan, a director of Trans World Airlines, who discovered and photographed the pyramid. The New York Times even wrote an article about it on March 28, 1947, and there is this photograph (see Fig. 14 ??). In any case, all reports of Gaussman‘s 1945 story incorrectly include Sheahan‘s picture taken in 1947. As it was undoubtedly Sheahan who took the picture, this severely damages the credibility of Gaussman‘s statement.

Four hypotheses about the “White Pyramid” have arisen:

The problem is that, since the 1990s, we European pyramid researchers have attributed the picture to Gaussman and used it as the basis for our attempts to locate the “White Pyramid”, so these hypotheses are largely based on that attribution.

1. In 1995, Austrian Walter Hain was the first to publish the picture in the German-speaking world in his book “Das Marsgesicht” (it had already been published in 1986 in “The Face on Mars”, by Australian Brian Crowley and American professor J. J. Hurtak). In his book “Pyramiden in China”, published in 2009, Hain proved that the pyramid pictured was the Mao Ling pyramid by analyzing the pyramid‘s erosion and surroundings. Having conducted my own research and comparisons on site, I can confirm that Sheahan‘s photo shows the mausoleum of Mao Ling. This does not, however, disprove Gaussman‘s statement. Here is what Hain has to say about it:

“In 1978 the New Zealand researcher Bruce L. Cathie bothered itself of a clarification of the puzzle. According to some correspondence with the Chinese embassy and the US air force he kept up the photo of 1947. He published the picture later in the first edition of his book „The Bridge to Infinity“ of 1983. It is a pyramid with four flat trapezoid shaped sides, a square plateau on the top and a square base, like the pyramids in Egypt and in Mexico … They should be had found north of the contemporary city Sian (Xi´an), by the foot of the river Wei-ho – exact at 34.26 degrees of northern width and 108.52 degrees of eastern length. This data were for me very helpful when I searched in September 2006, with “Google Earth” over China after the pyramids. According to some trouble I then kept up after the coordinate information of Bruce L. Cathie two pyramids. As result, I found further, more than twenty and bigger pyramids. They are square earth-pillars, constructed by Chinese craftsmen a long time ago very obviously. The ‘white pyramid’ needs not to be a tremendous mystic building. The pilots and the travel agents to see the Maoling mausoleum, with his size – according to the measurements via Google Earth – of about 222 to 217 meters on the ground and his height of about 46 meters, can quite have appeared below glistening sunlight glimmering and quite big.”

(14.3 – Hain)

I verified these coordinates myself with GPS on site in June 2011, but as Hain writes, there were only the very flat earth pyramids. The coordinates Cathie gives for the “White Pyramid” are incorrect.

2. Russian author Maxim Yakovenko has written in recent years that it was the Qin Ling pyramid. I do not share his conclusions, except the one about the “shaped mountain”, but the one he mentions fits neither Sheahan’s photo nor Gaussman’s statement. And although that mountain, which has one northern and two southern peaks, has been officially categorized as a geological elevation, Yakovenko believes that the significantly higher northern elevation is the tip of an artificial pyramid. His claims are based on, among other things, the Australians‘ report from 1912: Mount Liang is also almost 300 meters high, measured from its base. He also provides a theory about Schröder‘s account of the mountain‘s colors: The mountain‘s west side is still covered with light gray stone blocks, which probably gave the mountain its modern name, “White Pyramid”. Regardless of the construction method used, he believes this to be one of the world’s highest pyramidal constructions. But it isn‘t. Not only is it not a man-made pyramid, but when I inspected all three summits myself, even the northern one turned out to be shaped from the rock and not made of piled-up material.

3. The German researcher Hartwig Hausdorf, who visited the region during the 1990s, concluded in his book “Die weiße Pyramide” that the “White Pyramid” is not among the Xi’an pyramids and has not yet been found. Erich von Däniken shares his opinion, as do I. I believe Gaussman saw the pyramid in the flatter parts of eastern Tibet while flying from India to China. The legends say that the pyramid has a tip made of crystal (see “Kailash”, page 147).

4. Many undocumented internet sources, mostly copies of each other, still claim that the “White Pyramid” is located in the region around Xi’an. Some believe it to be inside a restricted military area to the north of Xi’an because there is also a missile base in the region. But there are no facts or pictures, and even the locals knew nothing about them. Hence, the mystery of the White Pyramid remains unsolved.

Other Pyramids in China

Amazingly, there are other pyramids in China, built using different construction methods, and not simply made of piled-up earth. I will give three examples that almost deserve more attention than the earthen pyramids of Xi’an, as they are actual layered stone block pyramids, much like those in South America.

Layered stone pyramid of Jian/Zangkunchong (Goguryeo Dynasty)

There are two isolated layered pyramids near the city of Ji’an in Jangxi province in southeastern China. The perfectly preserved Ji’an pyramid is built of precisely cut stone blocks and contains a large burial chamber. Each base has a length of exactly 31.60 meters on every side, and the height is 12.4 meters. It is made up of seven layers, the first of four layers of stone, and all others of three. This layout is surprisingly similar to that of the layered pyramids in South America. The twelve monoliths that were placed so as to lean against the outer walls’ lower layers – the largest of which is 2.7 meters wide and 4.5 meters high – also set this one apart from other Chinese pyramids. Of these twelve monoliths, four are so-called guardian stones, but only “Paechong” (Korean for “warden‘s tomb”) is still intact. Interestingly, the pyramid is oriented to the cardinal points, while the heads of the stone sarcophagi in the chamber pointed precisely to the mystical volcanic crater of Paektusan (Mount Paektu) on the horizon with its beautiful crater lake at an altitude of 2,500 meters.

There are three hypotheses about who built it:

– The first suggests that it was built during the ancient Goguryeo empire, which briefly ruled Korea and parts of eastern China, as a stone mausoleum for King Kwangkaeto the Great (Gwangaeto, 374-413 AD). He is also credited with the construction of the nearby stone pyramid that is almost completely destroyed. The foundation walls, with their base lengths of almost 40 meters, are all that remain of that pyramid, which is thought to be his tomb.

– The second posits that the remaining pyramid is the tomb of King Zangsu (Jangsu), which is why it is called “Zangkunchong”. It is also called Juni Ten (the general’s tomb) and “Pyramid of the East”. This name comes from the 20th regent of Goguryeo, the northernmost of the three Korean kingdoms, whose capital was Ji’an. Historical documents state that king Jansu was crowned king in 413 AD at the young age of 19 and went on to lead the kingdom, stretching from Korea to Mongolia, to its golden age. He died in 491 AD. But how did the Goguryeo Dynasty acquire the knowledge necessary for the construction of such flawless layered pyramids, the likes of which had never been seen in the area, and were not seen there again?

– The third hypothesis posits that the pyramids were built during the Kokuryo period, around 500 AD. That theory does not name the ruler who is buried there.

Xia Pyramids (Xia Dynasty), made of clay bricks

The Xia pyramids are located in western China, on the eastern slope of the Helan mountains, about 35 kilometers west of Yinchuan, the capital of the autonomous region of Ningxia Hui. They consist of pyramidal mausoleums for the imperial family with heights of between 9 and 20 meters, and 207 documented stone tombs for nobles and higher magistrates, all scattered over an area of 40 km2. Chinese researchers have conducted archaeological and scientific analyses on these tombs since the 1980s, but the sudden rise and fall of the western Xia dynasty (also referred to as the Tangut Empire, 1038-1227) remains a mystery. One theory suggests that they were overrun and largely eradicated by invading Mongols under Genghis Khan. The best-preserved burial pyramid (Mausoleum No. 3) is the only one to have been excavated and explored. It was attributed to the first Xia emperor, Jingzong (1003-1048), whose birth name was Li Yuanhao. The pyramids were built with clay tiles, and the construction method used combines elements from the construction of pyramids, towers and traditional temple-mausoleums, while the chambers feature Buddhist elements and paintings, although these might have been added later.

Stone and earth Xituanshan Pyramid near Jiaohe

The ruins of Xituanshan, near the city of Jiaohe, on the border of the Taklamakan Desert, were excavated in 1950 after water erosion exposed the first two tombs (see sunken desert cities on page 586). The entire complex spans an area of 1,000 meters x 500 meters for a total area of 500,000 m2. Historical accounts state that it was the capital of the Chesi Empire from about 108 BC to 450 AD. But in 2006, Chinese archaeologists dug deeper and uncovered a group of six much older tombs that are thought to date back to the Bronze Age, or 1,000 BC, making them 3,000 years old, or almost 1,000 years older than the Chesi empire. For five of the pyramidal structures, only parts of the foundations and first layers remain, but these still reveal their original shape and size. The largest pyramidal tomb has been clearly identified as a three-layered pyramid made of stones and earth. It has a square base of 50 meters x 30 meters and an oval platform of 15 meters x 10 meters at its apex, on which stood a stone sarcophagus covered with a granite plate and surrounded by four engraved stone tablets. This mysterious sarcophagus and the pyramidal tombs were attributed to the “king of an earlier tribe”. I am certain that this complex was built by the legendary Sand People.

Stone and earth Hongshan Pyramids near Sijiazi

In the autonomous province of Inner Mongolia in northeastern China, a 5,000-year-old, three-tiered pyramid was discovered on a shaped-hill pyramid north of the city of Sijiazi in Aohan County. Even Chinese archaeologists immediately recognized it as a man-made pyramid, specifically as a burial complex from the Hongshan Culture (4,500-2,250 BC). The tiered pyramid is said to be about 30 meters long and 15 meters wide, and an altar and seven graves were found on its platform. In the graves, besides the remains, were various vaults containing a bone flute, a stone ring and the stone statue of a goddess. The archaeologists also discovered clay fragments with small stars scratched into their interiors which they believed to indicate either an early culture’s astronomical knowledge or a mythology that indicated that they would one day return to the stars.

Pyramids in Tibet

For information on the pyramid near Mount Kailash and the “White Pyramid” in the Yarlung Valley in the province of Tibet (see “Kailash”, page 147).

This is just a small excerpt from the book GAIA LEGACY.